Sprigman Throws a Definition at Blake Morgan

The Spitting Image of the Modern Major General

MTP readers may remember the name Christopher Sprigman. Most recently, we have identified him as a counsel to Spotify in the “Nashville cases” brought against his firm’s client Spotify by four plaintiffs represented by well-known and successful artist rights attorney Richard Busch. These were cases brought against Spotify in Nashville for claims of copyright infringement by independent publishers who opted out of both the NMPA settlement and the Lowery & Ferrick class actions. (Just to be clear, Lowery had nothing to do with the Nashville cases.)

Professor Sprigman also teaches at the New York University law school in New York and evidently has an of counsel relationship with the distinguished New York law firm Simpson Thatcher. According to his law firm biography:

“Chris is a tenured faculty member and Co-Director of the Engelberg Center on Innovation Law and Policy at New York University School of Law, where he teaches intellectual property law, antitrust law, competition policy and comparative constitutional law.”

Simpson Thatcher is one of those ultra white-shoe corporate law firms, a very conservative reputation and also highly respected around the world.

Pot, meet kettle

Professor Sprigman has a history in copyright circles dating back to at least 2002, i.e., before he worked on Simpson Thatcher client Spotify. His selection to represent Spotify may be explained as simply as Professor Lessig was not available, but it’s more likely that his past work informed his selection as is usually the case. Nothing wrong with that.

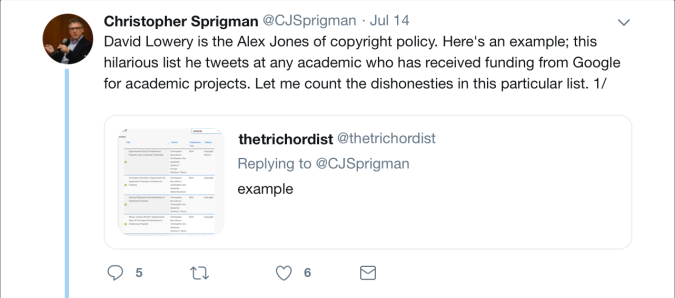

Some of Sprigman’s academic writings can be found on his SSRN author profile. At least a few of these papers (that we know of) were co-funded by Google. That Google connection evidently is a topic of some sensitivity with Professor Sprigman as it was that point that seems to have prompted his unprovoked and public comparison of David Lowery to Alex Jones.

Aside from the depressing reliability of the Alex Jones Corollary to Godwin’s Law, this was both a shocking yet curious comparison. Why Alex Jones, of all people? What about Alex Jones is of relevance to David’s role in the artist rights struggle? I am of the view that it carried with it an implied threat–Sprigman could get his buddies in Big Tech to deplatform David just like Alex Jones. Why? My guess is that it is because Sprigman apparently wants you to believe that David’s message was just as toxic to Twitter. (David was not even involved in the initial Sprigman exchange at all and tells me he had no idea it was even going on. He was on the road with Cracker and Camper Van Beethoven, you know, selling T-shirts like a good boy.)

The non denial denial

It All Starts with the Disney Fetish

Professor Sprigman has a long-term connection to Professor Lessig, beginning with a 2002 article “The Mouse the Ate the Public Domain” supporting Lessig’s losing argument in Eldred v. Ashcroft attacking the 1998 Copyright Term Extension Act. (“Most artists, if pressed, will admit that the true mother of invention in the arts is not necessity, but theft.” How very 1999.)

It will not be surprising to learn from the NYU alumni blog introducing Professor Sprigman that Lessig is his “mentor” (“Sprigman set a goal of writing an article within four months that he could take on the job market, if his mentor and the [Stanford Center for the Internet and Society]’s founder Lawrence Lessig deemed it satisfactory. The result was a paper that reintroduced the idea of formalities in copyright law. Its boldness won Lessig’s approval.”) Ah, yes. Fortune favors the “bold.”

A younger and perhaps bolder Sprigman held a 2003 fellowship at Stanford’s Center for the Internet and Society (founded by the very bold Lawrence Lessig III and later funded by the even bolder Google in 2006 with a $2 million gift). This academic fellowship evidently produced his 2004 article “(Re)Formalizing Copyright” boldly published by Stanford and, in a nutshell, advocating a requirement of copyright registration. (My view of this fascination that many of the Lessig crowd have with registrations is to create a giant loophole that would allow Big Tech to use “unregistered” copyrights (especially photographs) as they saw fit. Boldly, of course.)

As a quick aside, MTP readers will recall that the “address unknown” NOI debacle makes clear that even if works are registered and readily available through searchable databases that currently exist, Google, Amazon, Spotify and some others cannot be trusted to look for the sainted registrations. These companies appear not to have looked or not to have looked very hard before attesting that they had searched the Copyright Office records in their 70 million or so address unknown filings. Even allocating 5 minutes per copyright for search time, it would have taken over 350,000,000 minutes. Feel me? Curiously, Apple never used the address unknown loophole. It is unlikely that a registration-based system (which the US abandoned decades ago) would produce the promised results but would produce a substantial burden on all copyright owners, especially independents–not to mention the productivity loss to the Copyright Office itself.

This registration loophole is also a core Lessig concept that he pushed during the orphan works bills of the 2006-2008 period (see “Little Orphan Artworks”. It is echoed in the Music Modernization Act with the requirements to register with the Mechanical Licensing Collective under Title I (at least if you want to be paid outside of the black box) and the registration requirements under Title II for pre-72 copyright owners imposed by Big Tech’s favorite senator, Ron Wyden. Note neither requirement requires a formal copyright registration so doesn’t go as far as Lessig, Samuelson and Sprigman, but it’s headed that direction.

Sprigman later was co-author with Lessig of the Creative Commons filing to “save” “Jewish cultural music” in 2005 orphan works consultation by Copyright Office.

In 2006, Professor Sprigman was lead counsel with Lessig on the losing side in Kahle v. Ashcroft (later v. Gonzales) which unsuccessfully challenged the elimination of the renewal requirement under the 1992 Copyright Renewal Act. He went on to write “The 99 Cent Question” in 2006 attacking iTunes pricing.

Association with Pamela Samuelson

Pamela Samuelson is another registration fan in the professoriate, so it was not unexpected that Samuelson and Sprigman would find each other. Among his other accomplishments, Professor Sprigman was a member of Pamela Samuelson’s “Copyright Principles” project and co-authored its paper that also advocated registration (see Sec. IIIA of paper, “Reinvigorating Copyright Registration”). (MTP readers will remember Samuelson and her husband the tech maven Robert Glushko from the Samuelson-Glushko IP units at various law schools in the US and Canada that consistently oppose artist rights. A critic might say that the Samuelson-Glushko academic institutes are like Silicon Valley’s version of Confucius Institutes.)

The Copyright Principles Project is especially relevant to Professor Sprigman’s outburst regarding David Lowery because of what I would characterize as the utter failure of Pamela Samuelson to make an impact when she testified before the House Judiciary Committee’s IP subcommittee in 2013. This missed opportunity was, I think, largely due to Lowery’s takedown of the “Project” that appeared in Politico hours before she testified which Chairman Goodlatte asked to be entered into the record of the hearing where it sits to this day.

It’s worth noting that there were no creator members of the Copyright Principles Project, and Samuelson was questioned sharply about this by the IP subcommittee–it sounded like staff had been fed the “Case Study for Consensus Building” without being told that an important group had been omitted from the “consensus”. Her response was that she didn’t need any creator members on the Copyright Principles Project because she was herself an academic writer. I think it’s fair to say that while I didn’t see any of the Members laugh out loud, her response was viewed as rather weak sauce in light of Lowery’s post in Politico. That exchange appears to have led to Samuelson founding the “Authors Alliance” after the hearing evidently to shore up that shortcoming. Too late for the Copyright Principles Project, however.

All Hail the Pirate King

Like his mentor Lessig, Professor Sprigman also seems to have an interest in defending the alleged benefits of piracy and apparently is a leader of the “IP without IP” movement (and co-author of the piracy apologia, The Knockoff Economy: How Imitation Sparks Innovation.) (See also what we call the “pro-piracy” article “Let Them Eat Fake Cake: The Rational Weakness of China’s Anti-Counterfeiting Policy“. “[M]ost of that harm [of counterfeits and piracy], at present and for the foreseeable future, falls on foreign manufacturers”–this means you, songwriters.) He frequently writes on pro-piracy topics with Professor Kal Raustiala of the UCLA School of Law of all places.

It should come as no surprise then, that he represented Spotify in the Nashville cases. He was co-counsel on Spotify’s papers (with Jeffrey Ostrow from Simpson Thatcher) famously making the losing argument that, in short, lead to the conclusion that there is no mechanical royalty for streaming (after the usual Lessig-esque Rube Goldberg-like logic back flips). In Sprigman’s America, his Big Tech clients would not pay streaming mechanicals to Spotify at all, an issue that was emphatically put to rest in the Music Modernization Act. (In a curious case of simultaneous creation, Techdirt came to almost the identically flimsy argument.)

What Did We Ever Do to Him?

But before last week, Professor Sprigman most recently came onto the radar in his chairing of the American Law Institute’s Restatement of Copyright which many (including me) view as a political end-run around the legislative process. Register of Copyright Karyn Temple said the Restatement of Copyright “appears to create a pseudo-version of the Copyright Act” and would establish a contrarian view of copyright under the mantle of the august American Law Institute. It’s unclear to me who, if anyone, is financing the Restatement. (MTP readers will recall The American Law Institute’s Restatement Scandal: The Futility of False “Unity”.)

Aside from the fact that the normal world is not waiting for the Restatement of Copyright, it is hard to understand how a person with such overtly toxic attitudes toward uppity artists like Blake Morgan, David Lowery and David Poe should–or would even want to–participate in drafting the Restatement.

Unless they had a reason. Like providing a citable text holding that piracy is groovy, for example. Originalists come not here.

It’s not difficult to understand the creative community’s unease when taking a closer look at two of the projects leaders. The Restatement was originally the idea of Pamela Samuelson, a Professor of Law at UC Berkeley who is well known in the copyright academy as someone who has routinely advocated for a narrower scope of copyright protection. And while her knowledge and expertise in the field is unquestionable, her ability to take an objective approach to a project meant to influence important copyright law decisions is suspect.

While Professor Samuelson’s academic record reveals that she may not be the most suitable candidate to spearhead a restatement of copyright law, the project’s Reporters—those responsible for drafting the restatement—are led by Professor Chris Sprigman, whose work in academia and as a practicing attorney should undeniably disqualify him from this highly influential role.

Yet as of this writing, the American Law Institute still lists Professor Sprigman as the “reporter” of its Copyright Restatement project.

As one artist asked me of Sprigman, what drives him to be so consistently on the wrong side? What did we ever do to him?

(h/t to Fox of TO)

[from https://ift.tt/2llz3cO]

No comments:

Post a Comment