Fandom convention shows can make for fun, fantastic gigs, but while these performances can be laid back, they require the same (if not more) amount of planning as any other show, particularly if you want to avoid getting on the bad side of those staffing the con.

_________________________

Guest post by indie musician Matthew Ebel

I’ve played fandom convention shows exclusively for the past decade. They’re fun, laid-back, and some of the best parties I’ve ever been a party to. I’ve learned, however, that the planning and execution has to be handled as thoroughly as any other concert. From the booking process to signing autographs after the show, preparation and professionalism will make everyone’s lives easier (read: will get you invited back for next year’s convention). Here’s what I’ve learned in ten years of touring:

IN GENERAL

Convention staffers are largely volunteers.

“Director of Programming/Events/Music/Dances/Etc.” may sound like an impressive title, but chances are it’s a software engineer who spends her after-hours time making a convention happen instead of playing video games. They do this for the love of the fandom. Treat them like you’re asking for a resource more scarce than gold: their time.

Don’t be a diva.

I mean, this is true whether you’re playing the Grand Ole Opry, a coffee house, or SDCC. We need a healthy amount of ego to survive as performers, but the real professionals are polite, patient, and accommodating with the folks working to make their show better.

To quote Wilm Pierson, VP at Complete Production Systems, Inc.:

It is good not to forget that the stagehands, designers and directors are artists and craftsman as well and want to make the show amazing, so be kind.

BOOKING

Email early, email often.

Sometimes it seems like convention programming is all thrown together a week before the event. It’s not. Even if I’ve played a convention several times, I ask my contact (usually the Director of Programming) when the best time to reach out for next year’s con will be. Some of them start work a week after the con ends, some begin the process at the six-month mark. No matter what, asking what’s convenient for someone else shows that you care about their sanity.

Be ready to explain your act in 1-3 sentences.

I know, you’ve got a story to tell. You’re amazing in so many ways. So’s every other act vying for limited stage time. Condense your pitch down to a line or two and you’re more likely to get a response. Then back it up with properly made booking materials.

Properly Made Booking Materials

The One-Sheet

A must-have for any booking process is the one-sheet. It’s your resumé/CV as a performer. This gives the programming lead a single page to peruse and pass around to their staff. The essential ingredients are:

- A clear, professionally-shot photo, preferably from a live show.

- Your act name. (Dear God, I wish I didn’t have to mention this, but I do.)

- What you do. Say it in a few words or less. “House/Trance DJ,” “Punk Rock Trio,” “Mos Eisley Belly Dance Troupe,” whatever.

- One-column bio. I’m not going to re-hash the bio-writing basics, you can find those all over the indie-musician websites.

- Links. Your website and social profiles. Chances are good the convention’s PR staff will copy/paste these links to their website and programming materials.

- Your demos. You should have at least a one-song studio demo posted and downloadable online. You’re better off with live concert video and audio so the programming staff can see and hear exactly what you do. Film a live performance in your garage if you have to.

- Link to your tech rider. More on the tech rider shortly.

- Booking contact info. Put the actual legal name of your act’s booking contact (most likely you if you’re reading this) in the footer along with an email address and phone number. Get a Google Voice number if you’re shy about handing out your info, just make sure you can be texted/called on-site during the convention.

- Venues you’ve played previously. (Optional, but recommended.) If you’re a new act, obviously this one’s gonna be tough. But if you’ve played some big shows– even two or three of them –it’s a good idea to list them on the one-sheet.

The Tech Rider

A “rider”is typically something attached to a larger contract, but in this sense it’s simply your technical info. Remember: in order to put you on stage, someone has to plug all your stuff into electricity and audio. “I’m just a solo singer/songwriter” doesn’t cut it. That could mean anything from simple acoustic guitar/vocal to a complicated looping pedal and backing track setup with a mess of inputs and power requirements.

Be very specific about your on-stage needs, and don’t fucking change them. Convention programming has to incorporate setup and teardown into their scheduling. Your set may only be 60 minutes, but if your setup jumps from 15 minutes to 30 because you added a guitarist the day before your show, you’re not making any friends.

Also, “I played this show last year so they know my setup” doesn’t cut it either. Convention staff fluctuates. They also work with lots of acts besides yours, possibly at multiple conventions. Even if you handed them the same tech rider last year, give them the tech rider this year too.

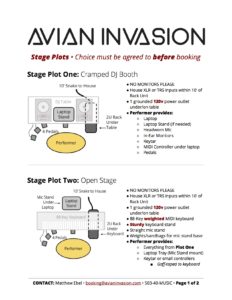

I keep my tech rider as simple as possible. Simple = less headache for the A/V crew = better chances of being invited back. The most important parts are the Stage Plot and Channel List.

Stage Plot(s)

A clear drawing of what the stage will look like during your act. This lets the A/V crew spring into action with minimal on-stage confusion during setup. You might have a few options (as I do) for large, medium, and small stages. Give them all to the A/V crew and let them decide what will work for the real estate they’ve got. The important parts are:

- Where everyone will stand on stage

- Where your equipment (amps, keyboards, drums, props, tables, stands) will sit

- Where the house’s equipment (if any) will sit– things like mic stands, amps, monitors, etc.

- Where you need power (how many outlets and, if possible, what kind of current your gear draws)

- Where you need audio (and make sure you specify XLR, TRS, phono, etc., even if it’s also covered in your channel list)

Remember that not all stages are the same size. If you need to be exactly ten feet away from your bassist, put it in writing but be ready to adjust your setup if the stage is small.

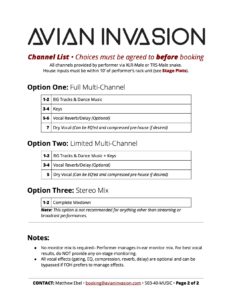

Channel List

Your exact, unchanging input/output needs. I cannot stress how important this is. The A/V crew has no idea whether you want to mic an amp or go direct. They may have different drum mic capabilities than your garage setup. Again, it’s not a bad idea to have several options for various A/V setups; I’ve played shows with 64-channel digital mixers and 4-channel amp heads. Be prepared for the full gamut of house gear.

For each of your input/output options, be sure to list the following:

- What type of physical connection (XLR Male, 1/4″ TRS, RCA stereo, etc.)

- Mono or Stereo

- A brief description of the input/output type (i.e. “Lead vocal mic”, “Backing tracks line out”, “In-ear monitor feed from house”)

I run all my on-stage outputs through my own mixer and feed the house an 8-channel XLR snake. This tends to make A/V crews very happy since it’s predictable and all the hookups are in one spot.

Also, like I said before, don’t fucking change your input/output scheme after you’ve been booked. It’s really not cool.

Other Requirements

Your estimated setup/strike times will help programming work you into the schedule flow, but you must be flexible.And the shorter the time requirements, the better. You want to be treated like a professional? Act like one. Run setup and strike drills on your own time in your own rehearsal space. Figure out what gear and steps you can eliminate to make the process faster. Be ready to delegate tasks to volunteers (i.e. “coil those cables” or “unplug everything from that amp and take it backstage”).

Your goal is to make your setup and strike processes look like a NASCAR pit crew in action.

The tech rider is where you can easily rule yourself out as a performing guest. Yeah, a green room stocked with beer and caviar might be nice, but you’re not going to get it. At conventions, chances are good you won’t even get a green room at all. Keep your requirements to the bare-ass minimum– it’s better for you in the long run anyway.

Programming Info

Aside from your show, you can probably lead or participate in panels and events. Offer up a menu of options for the programming staff with short descriptions they can drop directly into their con books. Most cons need good programming, and leading a few panels helps raise your visibility with the attendees. I typically host a three-part series on turning your art into a business, something a LOT of attendees appreciate.

You should also have multiple lengths of bio available: The feature-length bio for the convention’s website or con book, the paragraph-length bio for blog posts and panel info, and a tweet-length bio for social media posts and the mini-schedule.

AT THE CONVENTION

So you’ve gotten the gig, you’re checked into the hotel, and you’ve washed the airplane funk from your body. Now what?

Survey The Battlefield

Get to know the convention space early. An unfamiliar hotel can feel like a rabbit warren, which is the last thing you want to be stuck in when you’re late for your own show. Figure out where attendee-only areas are and always keep your badge displayed. Look at ingress/egress options before the place gets crowded– can you avoid elevator lines by taking the stairs? One year at FWA I descended 18 flights of stairs because the hotel’s elevators were slammed and I had a panel to lead in ten minutes.

I also like to survey the venue I’ll be performing in before things get busy. Check out the stage size, the lighting, access to the backstage area, possible merch table locations, etc. Go shake hands with the A/V crew and thank them in advance for their work. Remember: your show is in their hands. Keep them happy. I typically will chat with them for five or ten minutes while they’re setting up, then GTFO so they can do their jobs.

Confirm Your Timing With A/V

Programming may have worked you into specific time slots, but in the end it’s the A/V crew who control your destiny. Find a time when they’re not too busy (late morning to early afternoon is typical) and go over your schedule timing with them.

In some cases, they may prefer a setup/sound check time that’s hours before your actual show. Take this opportunity. If the convention’s running a digital sound board and lighting controller, they can dial in your mix and monitor levels while everyone else is still getting breakfast and just recall the settings later. You might even be able to leave your gear setup on stage or ready-to-deploy backstage, saving steps when it’s go time.

That being said, remember that the A/V crew needs sleep and food just like everyone else. If there’s late-night programming like dances or movies, they may have been working until 5 A.M. The fact that they’re not back at the mixing board by 9 A.M. doesn’t mean they’re lazy. If half the crew vanishes during your setup time, they may be emptying their bladders and stuffing food into their faces for fifteen minutes before going back to work.

SHOW UP EARLY.

Show up early. No, seriously, catch the last half of the act before yours. Maybe the whole act. Something may have blown up, leaving you with half the available audio inputs. Your backstage gear may have been moved because it was blocking a stage egress point. You never know what you may need to unfuck at the last minute. Or, rarely, a miracle may have occurred and the preceding act may have ended early, allowing you to set up at a leisurely pace. You never know.

Most of all, appearing backstage 30 seconds before your call time stresses the stage manager the fuck out. Eat your dinner at 4pm like a baby boomer and get your ass to the stage long before your call time and you’ll have a happy crew ready to pour their hearts into making you look good.

And that’s why you show up early.

Show.

Up.

Early.

DON’T EXPECT ANYTHING

As I said earlier, you probably won’t have a green room. Warm up in your hotel room before heading down to the stage. Be prepared to go on without a sound check if the preceding event runs 90 minutes past its time slot (I’m looking at YOU, every fursuit dance competition). Let the convention staff be apologetic and show them nothing but grace. Nothing ever goes according to plan; how you handle unexpected changes is how the staff will remember you.Treat them well and they’ll try to make your show better next year (and, most importantly, there will be a next year).

No comments:

Post a Comment